|

Ofcom: An evaluation of UK broadcast journalism regulation of news and current affairs Recent revelations about journalism ethics in the UK have thrown regulation of the media into the spotlight with the Press Complaints Commission found wanting and suggestions of change for the Office of Communication, the broadcast regulator, making this an ideal time to evaluate its performance. Amongst other duties, Ofcom is responsible for accepting and adjudicating complaints about editorial and programme content from viewers and listeners. Ofcom has received between 5,000 and 30,000 complaints a year, depending on whether some incident catches the public imagination. This paper analyses the thousand or so complaints adjudicated by Ofcom in the period 2004 to 2010 to identify how effective Ofcom is at dealing with complaints, particularly those about news and current affairs. The paper also aims to gain some insight into how Ofcom's adjudications affect programme makers' decisions. Keywords: Ofcom, Office of Communications, regulation, broadcasting, journalism, complaints Introduction Ofcom, the UK’s broadcasting regulatory body, came into existence in January 2003, set up by the Office of Communications Act 2002. Its main legal duties as set out by the Communications Act 2003, are:

Ofcom is funded by fees from industry levied for regulating broadcasting and communications networks; and grant-in-aid from the government. It is answerable to the UK Parliament but is independent of the UK Government. At a time when UK media regulation is undergoing its most critical assessment from the public and parliament, including the Leveson inquiry set up by the government in the wake of the Milly Dowler phone hacking revelations and the closure of the News of the World, this paper will look at Ofcom’s activities. Although broadcasting has so far largely avoided the criticism heaped on the national press for illegal activities it is an ideal time to examine how Ofcom carries out its regulatory duties enforcing its obligation to protect viewers and listeners (especially minors) from harmful or offensive material and to protect those who might appear in programmes from unfair treatment or invasion of privacy. The paper will attempt to identify trends in complaints and to examine particularly any lessons that can be learnt from complaints about news and current affairs. People wanting to complain about broadcasting standards or unfair treatment in TV or radio programmes in the UK can complain to Ofcom. Ofcom advises them to contact the broadcaster first, complaining to Ofcom only if unsatisfied with the response, but that is not essential. Complainants are required to complete a complaints form that is available online or can be ordered by post or by phone. Once the complaint is received, Ofcom will carry out an initial assessment to decide if there is a case to investigate. If it feels there has been a potential breach of its code, it will proceed to review the programme, providing details of the complaint to the broadcaster and seek a response. After considering the complaint and the broadcaster's response Ofcom’s content board will then reach a decision about whether the complaint is upheld, not upheld or has been resolved. Board decisions are published on the Ofcom website in a fortnightly bulletin. Some more serious breaches may require that the broadcaster broadcast the adjudication at an appropriate time and in the most serious cases the sanction can include a financial penalty or even a suspension or removal of licence to broadcast. Data gathering Data for this study were gathered from Ofcom reports (www.ofcom.org.uk). Ofcom publishes two types of report:

The fortnightly complaints bulletins allow Ofcom to identify the programme complained of, the broadcaster, the clause of the code complained of and the outcome of Ofcom’s adjudication. In the case of fairness and privacy complaints it also identifies the complainant. It does not do this for standards cases, partly because it is not significant and partly because there may be more than one complainant. For instance, in the Ross/Brand case there were thousands of complainants. The detailed data contained within the bulletins were all logged onto a database allowing them to be filtered and manipulated in a way that best allowed analysis. In order to identify programmes that were broadcast by radio as opposed to those broadcast as TV and in order to identify programmes that were news or current affairs each was tagged if it was radio, or if it was news and current affairs. News and current affairs programmes were identified as being programmes that:

These included News at Ten, Newsnight, Panorama, Despatches and local news services. Programmes that although factually based were either reality television, educational programmes or contained no (or very little news) current affairs such as Motorway Cops, Neighbours from Hell, Police, Camera, Action, cookery or nature programmes were excluded from this category. Tables of data were also extracted from Ofcom annual reports to show total complaints made and programmes complained about. These are identified separately in the analysis below. The aim of analysing these data is to identify how effective Ofcom is at dealing with complaints and to gain some insight into how its adjudications affect programme makers and their decision making. Is Ofcom able to address the issues that are of real concern to viewers and listeners? Analysis of Ofcom complaints One way of analysing how effective Ofcom is as a regulator of editorial content in programmes broadcast by licence holders in the UK is to measure the number of complaints made and the responses those complainants receive. There are three main categories of complaint:

Those complaints that do not allege breaches of the code cover everything from complaints about schedule changes to irritation at the ending of a favourite series. These are not pursued by Ofcom. Complaints that are potential breaches of the code are identified in Ofcom's fortnightly complaints bulletin. Ofcom’s broadcasting code Ofcom is required by the Communications Act 2003 to draw up a broadcasting code against which it can measure complaints made. This must cover programme standards (minors, impartiality, accuracy, harm and offence) and fairness and privacy.[4] The development of the two types of complaints (standards and fairness & privacy) is historical but covers the key areas of concern of legislators. Standards, including matters of taste and decency, violence, sex and bad language were under the control of the Broadcasting Standards Council, set up by Margaret Thatcher in 1988 and given statutory authority by the Broadcasting Act 1990. The Broadcasting Complaints Commission had been set up by the Broadcasting Act 1980 to consider complaints concerning unjust or unfair treatment or unwarranted invasions of privacy (Frost 2000: 188-189). The two were combined by the Broadcasting Act 1996 to become the Broadcasting Standards Commission. This covered the dual role of the two former bodies, looking at both standards and fairness & privacy. It sat alongside the Independent Television Commission and the Radio Authority who controlled the licensing arrangements for the independent TV and radio providers (ibid: 200). The BSC was obliged under the Act to produce a code and it relied on past codes, the BBC code and codes in use elsewhere to produce a code very similar to the one still in use today. This was taken over by Ofcom when it replaced the BSC, ITC and Radio Authority in 2003. The key difference with regard to the code was the legislative decision to replace ‘taste and decency’ with ‘harm and offence’. These new terms are more specific allowing measurement by regulators rather than personal judgement. Offence can be determined to have taken place even if one disagrees it is justified and so regulators need only decide if the offence taken was reasonable or unreasonable. Similarly, harm can be measured by the circumstances. Taste and decency is just that, a matter of taste. The new terms also fit much better with the times smacking less of censoriousness seen by many as unsuitable for the 21st century. The former BSC code was applied by Ofcom for its first year or so giving it time to consult on a new code that was introduced in 2005. This followed a similar pattern to previous codes and although a new consultation followed a couple of years later, the new code introduced for 2011 was little different covering standards (particularly with reference to minors), harm and offence (the newly updated and more specific names for taste and decency) and elections. The Ofcom code is broken into ten sections (see table 1). The majority of complaints made largely fall under section 1 (under 18s) and section 2 (harm and offence). Table 1: Ofcom code and its operation

Section 1: Protecting the Under-Eighteens Over the lifetime of Ofcom there have been three major issues that have drawn a large number of complaints. The first programme to attract large numbers of complainants was the BBC2 programme Jerry Springer: The opera broadcast on 8 January 2005. Critics claimed the programme was blasphemous, contained several hundred swearwords and was very damaging to young people. Ofcom received 8,860 post-transmission complaints whilst the BBC received 47,000 or so complaints before transmission and another 900 after broadcast. Channel Four was the next to trigger widespread protests when Ofcom received more than 45,000 complaints about alleged racism in Celebrity Big Brother (C4) in 2007-8. This was followed by the Russell Brand show (BBC Radio 2) in 2008-9 in which Russell Brand and his guest Jonathan Ross rang actor Andrew Sachs and left an offensive message on his answer machine. The show was broadcast on 18 October 2008 and two complaints were received by the BBC the next day. The Mail on Sunday ran a story that the BBC might be prosecuted for obscenity on 26 October and the number of complaints rose by a further 1,585. By the end of the week, the BBC had received 30,500 complaints. The final total was 42,851. Ofcom investigated having received 1,939 complaints by 25 October 2008 and in April it fined the BBC £80,000 for breaches of the privacy section of the broadcasting code and £70,000 for breaches of the harm and offence section.[5] These three were the biggest cases in terms of the number of complainants and therefore, presumably the amount of upset caused. How the analysis was done The analysis was carried out by compiling information on all the complaints taken up by Ofcom and published in its fortnightly bulletins. The data were compiled into a database giving access to all Ofcom’s decisions about complaints made. The database includes information about the outcome, the clause of the code against which the complaint was made, the programme and the broadcaster. Ofcom adjudicates on complaints concerning 200 to 300 programmes drawn from the many thousands of complaints it receives every year. Complaints may be unadjudicated either because they are duplicate complaints or because the complaint does not breach the broadcasting code. There are, therefore, three headline statistics (to March 2011):

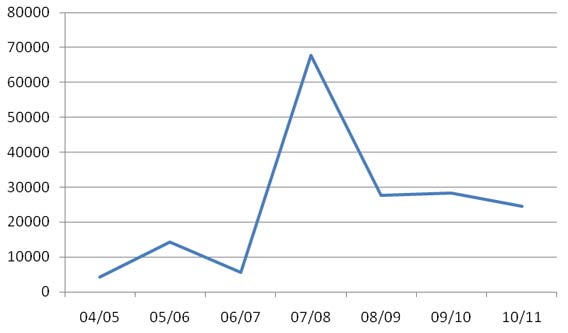

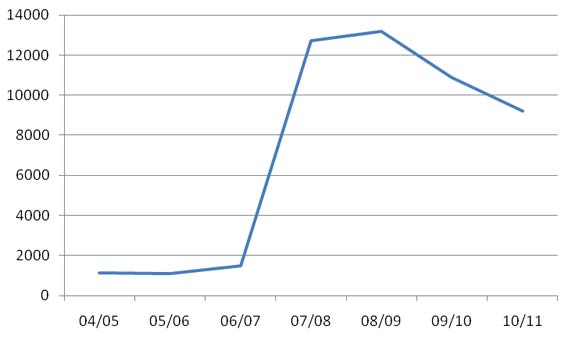

Ofcom receives a considerable number of complaints each year from viewers and listeners (see table two and figures one and two). Table 2: Complaints to Ofcom

Although the figures for ‘cases closed’ is reasonably steady for the first three years and then increases dramatically by more than 10,000 to remain reasonably static again for the next three years, complaints made numbers can vary wildly from just over 4,000 to more than 67,000. The number of complaints made reflects the number of complainants in any one year and so it is not possible to make any real judgement about the variation. Some issues spark large numbers of complainants raising the total in any particular year quite dramatically. Most of the very large increases are explained by complaints made about the high profile, controversial programmes mentioned above: Jerry Springer: The opera (BBC2); Celebrity Big Brother (C4) and The Russell Brand show (BBC Radio 2). If these complaints are factored out, the figures show that complaints made in the first three years are typically around 5,000 and in subsequent years around 25,000. ‘Cases closed’ refer to individual programmes complained about, rather than complaints. Typically in the first three years there are around 1,200 cases closed and subsequently around 12,000. This jump in both cases closed and complaints made is explained by a change in the way Ofcom has collected the data. When Ofcom first started operations, its Contact Centre logged and assessed the broadcasting complaints received by Ofcom and referred any that raised potentially substantive issues under the Broadcasting Code to the standards team for investigation. It was these complaints that were identified in the annual reports. However, from 2007/8 these data were no longer reported separately and so the much larger total number of complaints made to the contact centre (not just those referred to the standards team) were reported. An Ofcom spokesman said: This change in the way Ofcom reports on its broadcasting complaints was for the purpose of clarity, and to provide a single picture of the work Ofcom undertakes on regulating broadcasting standards. Therefore, while it appears there was a sudden increase in complaints, the number of cases has remained relatively consistent. Of course, as awareness of Ofcom and its role entered the public consciousness, an increase in complaints might be expected. Table 3: Complaints received by Ofcom’s standards team after redacting major causes of complaints identified above.

Figure 1: Complaints made to Ofcom

Figure 2: Programmes complained about

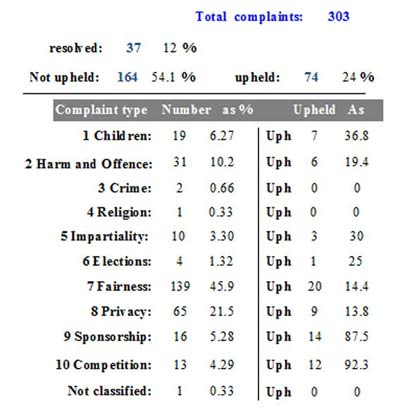

Ofcom investigates complaints made to it after an initial assessment that allows it to reject complaints that are not potential breaches of its code. It then publishes the results of its investigation and whether it has upheld the complaint in its fortnightly broadcast bulletin.[6] Table 4: All complaints listed in Ofcom bulletins

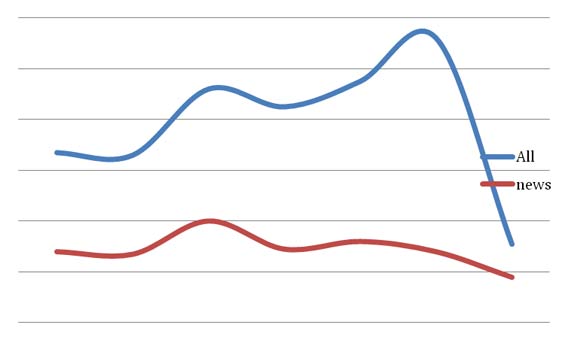

In its first seven years of operation, Ofcom adjudicated 1,522 complaints. These were complaints that allegedly breached its Broadcasting Code and that required Ofcom to reach a verdict. Of these 528 concerned privacy and fairness. Looking at all the complaints, the vast majority are not in breach of the broadcast code and so are rejected. On average each year 7,096 cases are not in breach of the code. An average of 168 standards cases per year are found to be in breach with 61% of the complaints upheld, an average of 15 involving sanctions. The remaining cases are resolved following some action from the broadcaster. An average of 78 fairness and privacy cases are dealt with each year of which 28 per cent are upheld. (see Table 4) News and current affairs Ofcom does not separate out its decisions on complaints made against news and current affairs and other programming. However, it is possible to identify news and current affairs programmes in the complaints bulletins and flag them in the database so that they can be calculated separately. For news and current affairs complaints, there is an average of 14.4 standards cases per year of which 47.4 per cent are upheld and an average 28.9 fairness and privacy cases per year of which 27% are upheld. This compares with an average 155.3 standards complaints about non-news programmes per year of which 62.1 per cent are upheld and an average 57.9 fairness and privacy cases per year of which 27.2 per cent are upheld (see Table 5). The biggest subject of complaint within news and current affairs is fairness closely followed by privacy with 112 complaints (48.5 per cent of the total) being about fairness and 51 complaints about privacy (22.1 per cent). There are fewer news and current affairs programme complaints than for other types of programme with a ratio of standards programmes complaints of 10.8:1 and for privacy and fairness complaints of 2:1. However, without calculating a ratio of transmitted news programmes to entertainment programmes (something that is outside the scope of this research) it is impossible to say whether this is significant. However, if the ratio of standards complaints in non-news and news are indicative of the ratio of entertainment and news and current affairs programmes, it is clear that the chances of news and current affairs intruding on someone’s privacy or treating them unfairly is much higher than for non-news programmes as the ratio of the number of news complaints is much higher. Since many non-news programmes are fictionally based or require active participation, this is probably not too surprising and may not mean anything. Table 5: Complaints about news and current affairs listed in Ofcom bulletins

Table 6: Complaints about other programmes listed in Ofcom bulletins

Table 7: Ofcom adjudications of news and current affairs complaints by type from 2004 to 2010

Figure 3: Fairness and privacy adjudications

Complaints made against the code sections listed above fall into two categories: those where the harm is done to the subject of the programme (or someone else in the programme) and those where the harm is done to the viewer. The key sections of the broadcast code for news and current affairs are privacy, fairness, impartiality and accuracy, children, harm and offence.

An analysis of all the complaints about news and current affairs adjudicated shows that the number of fairness and privacy cases upheld was fairly small: 20 for fairness and nine for privacy; fewer than one sixth of the complaints being upheld on adjudication in either case. Looking through the upheld standards cases, there are no obvious lessons to be learned other than continued vigilance over code issues. However, on privacy and fairness it is possible to categorise and consider several types of complaint. Two of the privacy and fairness complaints concern candid filming that risked being intrusive at the scene: the first a woman filmed during a police drugs raid and the second a woman filmed at the scene of a traffic accident in which her daughter died. In both, Ofcom decided that the broadcasts were unfair and had invaded the women’s privacy and should not have been broadcast. Neither was considered to have been intrusive at the time of filming as had there been a strong enough public interest reason for broadcasting then Ofcom might have accepted that transmission was justified. Several of the unfairness complaints concerned interviewee expectations. It is difficult to tell through the filter of the Ofcom bulletin whether these were errors of judgment, different expectations from interviewee and interviewer or simply the news bulletin failing to live up the promises made. The 18 upheld fairness complaints (some of which were also privacy complaints) covered the following issues that have been split into three main categories: Unfairness: Privacy and unfairness Complaints where intrusion into privacy was also judged to be unfair

Unfairness – reputation Complaints which were unfair because of choice of language

Complaints which were unfair because of implications made

Complaints which were unfair because there was no right to respond

Unfairness – sources Conduct of relationship with source did not go as promised

The broadcasters concerned were:

Privacy Privacy complaints covered the following issues:

From broadcasters:

Complaints under the children’s section concerned either violence or bad language. In two of the three language complaints the words were contained in the lyrics of pop songs. The programme had accidentally played the full version, not the ‘radio edit’ version of the recording. In one case, a story about child pornography, library footage had displayed website addresses for pornography sites which could have been easily read by children. ITV had three complaints upheld, whilst Sky, GEO News, Isles FM and OneFM each had one complaint upheld. This was considered a significant enough problem for Ofcom to have issued further guidance on 30 September 2011: ‘Ofcom warns TV broadcasters to be more careful around watershed.’[7] Three of the five harm and offence complaints concerned flashing lights, two against BBC1 and one against Sky. The Ofcom broadcast code warns against flashing lights as they may trigger photosensitive epilepsy. The other two complaints concerned a CCTV film of a late night knife attack (GMTV) and murder and an anti-Semitic joke on Radio Faza. Although all of the complaints that were upheld were breaches of the code, none was serious enough to warrant sanctions. Sanctions One of the major differences between Ofcom and the Press Complaints Commission is the power Ofcom has to levy sanctions against serious breaches of the broadcasting code. Ofcom is able, under statute, to reprimand a licence holder, levy a fine, suspend a licence or remove a licence altogether. It is the last two sanctions, relying on Ofcom’s power to grant or refuse licences to transmit, that are seen as particularly controversial when Ofcom is suggested as a model for press regulation. The government is obliged to have some system to regulate the airwaves, which are a finite resource, and so using this as a method to punish licence holders who regularly breach the broadcast code has some logic. Most commentators seem to view this as unacceptable for the press or web-based news outlets. Ofcom uses these powers infrequently and while it has suspended the occasional licence and even removed one altogether, these have been small specialist digital stations, involved in the soft porn end of the market. The majority of serious sanctions have been fines and, up to the end of 2010, Ofcom had fined stations a total of £6.221m averaging £135,239 a year. 2008 was a particularly punitive year with 19 programmes facing fines of £4,612,500, an average of £242,763. However, this was the year when competitions based on phone-in voting were run with many of them closing voting or being repeat broadcasts allowing the public to vote, even though their votes would not be counted. Granada Television, LWT and GCap Media Ltd were all fined more than £1m each. ITV2 and MTV were both fined in excess of £250,000. The BBC was involved in the Russell Brand affair and also had problems with Sport Relief, Children in Need Comic Relief and several radio shows and was fined a total of £495,000. Other penalties range from £2,500 to £1.2m with a typical penalty around the £50,000 level. It is worth noting that no news or factual programme in the study period has breached the code badly enough for Ofcom to consider a sanction. It is probably impossible to come up with a research method that would show whether penalties are successful in enforcing good practice. However, the general view from the public is that sanctions are likely to promote good behaviour and certainly large fines are not liked by shareholders, or (especially in the case of the BBC) by the public. The fact that sanction penalties fell significantly in 2009 following a number of serious incidents and then rose slightly the following year adds credence to this view, but is hardly incontrovertible evidence. Table 8: Total sanctions levied by Ofcom

However, the compliance routine of all major broadcasters, particularly but not solely the BBC, does much to maintain high standards. The requirement of evidence of discussion of ethical decision making and a contractual requirement to adhere to guidelines are contained in the BBC’s procedures and its compliance forms. Knowledge and proper implementation of the guidelines is central: When applying the guidelines, individual content producers are expected to make the necessary judgements in many areas, but some issues require careful consideration at a higher level. The guidelines therefore advise, and sometimes require, reference to more senior editorial figures, Editorial Policy or experts elsewhere in the BBC such as Programme Legal Advice (BBC Editorial Guidelines 2011: 2.2.3). Conclusion The recent outcries against the tabloid press and the setting up of the Leveson Inquiry has led a number of observers and politicians to wonder if broadcasting also has problems, whether Ofcom ought to be given a role in regulating the press or whether there should be a joint media regulator. The data here make it clear that complaints can be made about news and factual programmes and are taken seriously by Ofcom which is then able to take a serious line against transgressors. This seems to have enormously improved standards of journalism in broadcasting, with no evidence of increasing problems, no increase in complaints numbers and no significant problem complaints in the news and factual programming area. Most breaches seem to be mistakes, minor errors of judgement or misunderstandings. This is despite an open complaints procedure allowing all to complain and despite accepting complaints that concern harm and offence, neither of which is fully the case with the Press Complaints Commission. Ofcom also has the ability to levy sanctions, but has not needed to do that for a news programme. The PCC receives complaints mainly about accuracy (approximately 70 per cent) or privacy (20 per cent) whereas Ofcom’s biggest complaint category is fairness (46 per cent) followed by privacy (22 per cent) and harm and offence (10 per cent). There is of course some crossover between accuracy complaints to the PCC and fairness complaints to Ofcom. Many accuracy complaints made to the PCC are in reality about fairness or about offence. The PCC also does not accept complaints about harm and offence except in very limited circumstances. Tempting though it might be to have a cross-media regulator, these figures do suggest that there are different problems to address in broadcasting to newspapers. The final question is whether these figures show that Ofcom should have a role in regulating the press. Ofcom’s ability to levy sanctions means that the industry certainly seems to take it much more seriously than the newspaper industry takes the PCC, whatever editors say about taking PCC reprimands seriously in their evidence to Lord Justice Leveson. Ofcom’s guidance is noted and acted on and there is little evidence of repeat breaches in news programmes. The statutory support that Ofcom can rely on to enforce its decisions on all broadcasters, the openness of the complaints procedure and ability to impose sanctions are all elements that would strengthen press regulation and should be considered by Lord Justice Leveson, but the idea of a media council spanning all media would probably be a mistake. Despite convergence and the requirement for newspapers, magazines and broadcasters to have websites, a single media council would find it very difficult to give sufficient weight to newspapers and to broadcast news in comparison to the heavy load of TV entertainment programmes in a digital age that will see a steady growth of low-budget specialist channels. Leveson should look to Ofcom for ideas, but should ensure the press, and their websites, continue with their own, but much stronger, regulation. Notes [1] See http://www.ofcom.org.uk/about/what-is-ofcom/statutory-duties-and-regulatory-principles/, accessed on 24 November 2011 [2] See http://www.ofcom.org.uk/about/annual-reports-and-plans/annual-reports/, accessed on 16 October 2011 [3] See http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/enforcement/broadcast-bulletins/, accessed on 16 October 2011 [4] See C4 S319-328 Communications Act 2003. Available online at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/21/contents, accessed on 28 September 2011 [5] See http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/enforcement/content-sanctions-adjudications/BBCRadio2TheRussellBrandShow.pdf, accessed on 28 September 2011 [6] See http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/enforcement/broadcast-bulletins/, accessed on 28 September 2011 [7] See http://media.ofcom.org.uk/2011/09/30/ofcom-warns-tv-broadcasters-to-be-more-careful-around-watershed/, accessed on 28 September 2011 References

Note on the contributor Professor Chris Frost is Head of Journalism at Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK. He is the author of Journalism ethics and regulation (Pearson Education 2011, third edition), Media ethics and self-regulation (Longman 2000), Reporting for journalists (Routledge 2010, second edition) and Designing for newspapers and magazines (Routledge 2011, second edition). He is also chair of the NUJ's Ethics Council and a former President of the NUJ. Contact details: Department of Journalism, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool Innovation Park, Edge Lane, Liverpool L7 9NQ. Tel: 0151 231 4835; mobile: 07976 296777; email: c.p.frost@ljmu.ac.uk. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||